As the title suggests, the “Potty Talk” series will discuss defecation, digestion issues, and related parts of everyday life not usually discussed in polite company. If the thought offends, I suggest you read no further. Please enjoy my review of Dijon in ice cream instead.

Why, you may well ask, do I want to talk about poop, on the Internet of all places, where my future children, if I have them, will be able to find it someday–or worse yet, my future in-laws? Because A) it’s a universal experience, B) different cultures approach it differently, and C) I have fun stories to tell. And a good story is a good story, regardless of how puritanical our culture feels about the subject. Frankly, I’ve wanted to do this series for months now, but other topics always seemed more pressing. With my Facebook feed one more abuzz regarding the virtues of squatting, however, it seems the time has come.

–

I have a friend who’s a radio DJ, and because he’s the new guy at the station and therefore works the crummy weekend shifts, I like to call in to his show with song requests, answers to his questions, and veiled references to the camp where we both worked. The first time the temperatures dipped below 0˚F this winter, he asked his listeners about the craziest thing they’d ever been stuck doing out in the cold, so of course I had to call in.

“Does using an outhouse for a week in -20˚ weather count?”

Shuddering audibly, he assured me that it did and asked where in the world I’d been to have to do such a thing. And then he made the comment I’ve heard so many times from people trying to contemplate using an outhouse in below-zero weather: “Did you have to hover above the seat? I bet it must have been awfully cold!”

Seat? What seat?

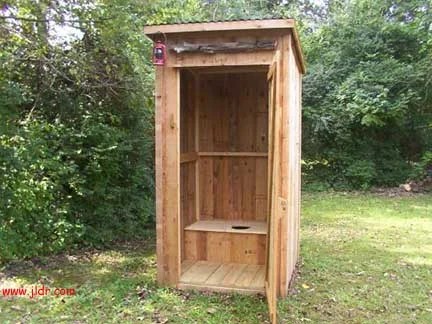

I suspect most Americans imagine outhouses to be like the one in Shrek: wooden buildings with raised seats, ideally with a lid to cover the the seat, and probably with a cute little moon-shaped cutout in the door. Those with more camping experience might picture latrines like the ones found in the boundaries, which are decidedly more… exposed in nature.

(Left, a lovely cedar seated outhouse; right, a more minimal BWCA latrine. Image credits in the alt text.)

(Left, a lovely cedar seated outhouse; right, a more minimal BWCA latrine. Image credits in the alt text.)

But even the bare-bones outdoor latrine has what I would consider the defining feature of a Western-style toilet: a seat.

This is not the case in Mongolia, where the setup is usually a wooden floor with a missing slat in the middle, through which you can see (and pee) down to the pit below. A nice outhouse is one with four walls, a door that can be latched closed, and a deep pit, but many lack doors and roofs; in the countryside, there may be little more than a shallow pit with two slats to stand on and three almost waist-high walls to provide a modicum of privacy.

Squatting over a hole in the floor instead of sitting on a porcelain chair isn’t a uniquely Mongolian thing, either. Even indoors, I’ve seen plenty of ceramic squat toilets in China and Thailand, some equipped with a flush mechanism and others simply with a bucket of water and a ladle. Generally speaking, I’d simply categorize this as a cultural difference between East and West.

In the case of the Mongolian outhouse, however, the design also serves a distinctly functional purpose. Imagine, if you dare, sitting bare-cheeked on a -20˚ seat–ow! At that temperature, just touching a door handle barehanded is painful enough, as I was reminded during the (overhyped) Polar Vortex. Worse yet, contemplate the possibility that the outhouse’s previous user was a little splashy, and that liquid hasn’t quite frozen yet. We all know what happens when you touch an ice cube with wet hands–it sticks. I suspect that the same thing could happen with a splashed-on outhouse seat, except that with that much skin involved, detaching oneself would be much more difficult. And if you can’t get unstuck yourself, and assistance is not forthcoming, you could literally freeze to death in the outhouse.

I can think of ways to die with less dignity… but not many.

So while using a Mongolian outhouse in the winter was a decidedly brisk experience, I was very glad not to risk freezing to the facilities every time I decided to use them. And a few months into my grant term, I learned that squat toilets had other benefits, too.

When this video first made the rounds, I was skeptical. As a long-time Girl and Venture Scout, I’d been using the outdoor “facilities” for years even before I traveled to Asia, and let me tell you: if you’re used to using a toilet, relieving yourself without one is NOT easy. Most Western women, when asked to pee in the woods, would probably do the same thing we do with dirty public toilet seats: hover in an approximately seated position–not because it makes much sense to do so when there’s no toilet to hover over, but because it’s what we’re used to. I did this at one point too.

The problem is that it doesn’t work very well. It’s extremely difficult to tense the muscles needed to hold you upright while simultaneously loosening the ones that release your bladder.

Even if you know you’re supposed to do a full squat, and that it supposedly allows you to void your bowels with less effort, it’s easier said than done. Most of us Westerners are apparently doing it wrong, since we ceased squatting in childhood and have let the necessary muscles atrophy:

Our on-the-toes method of squatting is less stable and harder to sustain, and I suspect instability is the last thing any of us want when crouching over a pit full of feces, especially if the boards we’re crouching on are icy.

I got this lovely diagram from an article on the health benefits of squatting that’s currently making the rounds on Facebook, but if you haven’t seen it and can’t be bothered to click through, the reasons it lists to squat are:

- ankle mobility

- back pain relief

- hip strengthening

- glute strengthening

- posture correction

- (possibly) decreased risk of arthritis

Whether I’ve seen any of these benefits from the time I spent squatting in this or that outhouse (and over the course of a year, it adds up!), I can’t say for sure, nor have I bothered to check out the medical studies cited for the Squatty Potty’s claims. But I can say that my ability to do a full squat has vastly improved in the past eighteen months, even if they only way I can sustain it for any length of time is by bracing my elbows against the insides of my knees à la malasana, the yoga prayer squat:

And the Squatty Potty’s claims that a “sensation of satisfactory bowel emptying” is easier to achieve when squatting, once you’ve learned to squat properly? Totally true. Which is especially important when emptying your bladder and/or bowels means putting on several layers, trekking out to the outhouse, and then taking some of them off (at least partway) in below-zero temperatures. Believe me, you don’t want to have to do that any more often than necessary.

So while I strongly appreciate the ability to use indoor facilities once more, there are times when I actually miss squat toilets. Amazing what some time abroad will do to your perceptions and preferences–even the most alimentary ones.

(You know I had to crack at least one poop joke in there. Sorry I’m not sorry.)